Barb Stinger, the descendant of Oregon pioneers, is also a “pioneer woman” herself, walking in the 40-day, 540-mile Oregon Trail Sesquicentennial Celebration reenactment in 1993 to celebrate the trail’s 150th anniversary.

“It was a once-in-a-lifetime experience,” Stinger said. “It is still a big part of my life. I am the historian of the family.”

The original Oregon Trail was a 2,170-mile-long trail between the Missouri River and Oregon, originally created by trappers and fur traders to be traversed on horseback or on foot. But starting in 1836 the trail was improved for wagon trains to use, eventually bringing 3,000 people west in the following years: 1836, 1845, 1852, 1853, 1860 and 1865, according to Stinger.

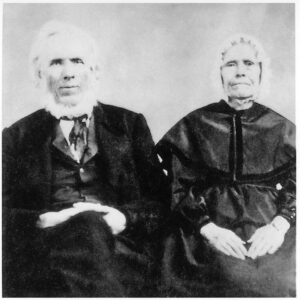

Her family was part of the 1852 wagon train but started their journey in Decatur County, Indiana, on April 15, 1851. Dr. Nathaniel Robbins (1793-1863) and his wife Nancy (1797-1880), Stinger’s great-great-great-grandparents, had 11 children, and the group of 24 people included their children and spouses. The group, which also included six hired help, traveled in 22 wagons, which were mostly farm wagons, according to Stinger. “They heard about free land in Oregon,” Stinger said. “It was paradise, and you could grow anything.”

The group wintered over in Huntsville, Missouri, and left March 19, 1852, taking one month to reach St. Joseph, which was the starting point of the Trail.

“In Nebraska, they traveled 25 miles a day and had to cross many rivers and also endure storms,” Stinger said. “On May 30, 1852, three daughters took sick with cholera and all died within hours of each other. A few days later a son-in-law died of cholera. The family was lucky because there was not a lot of interaction with Indians, but one offered six ponies for a 4-year-old girl with red hair. Of course, the family did not trade her, and they brought along gifts to buy off the Indians.”

At Independence Rock, they crossed the Platt River and lost 11 horses. The family remarked that when they crossed the Continental Divide, the streams flowed both east and west, and at Soda Springs, they made soda beer.

Traveling along the Snake River, they reached Salmon Falls, where they ate salmon for the first time thanks to the Indian traders. The steep trail into Baker City was hard on the animals and the people, and another daughter died outside Baker City.

“Their food was almost done, the cattle were worn out, and the wagons needed to be repaired or replaced,” Stinger said. “They stopped for a week in La Grande and decided to take a shorter route to The Dalles. On the Columbia River, the wagons were floated on flat boats, and small items were carried on wagons on the ‘railroad around the falls.’”

On Nov. 12, they arrived in Oregon City, seven months after they left St. Joseph. They settled on their donation land claim in the Tualatin area, and after surviving the Oregon Trail, Dr. Nathanial Robbins later drowned while paddling across the Tualatin River “to help someone,” Stinger said.

A remarkable footnote to the story is that the Robbins brought their thorn-less, moss-pink rose bush along on the wagon train, and it has been growing ever since for more than 166 years in Tualatin.

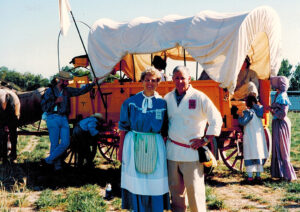

Stinger’s 540-mile journey from Palmer, Idaho, to Oregon City in 1993 was quite a bit easier. The modern-day wagon train consisted of 10 wagons that carried some people; the others walked or rode horses, and they covered 35 miles a day.

“It cost $40 per day, and we carried our own tent and sleeping bag, but there were cook wagons, and we ate very well,” she said. “And there were port-a-potties. Eight of us walked the entire Trail, and seven were women, and we became friends. I took two pioneer dresses to wear and black tennis shoes – I still have them – and my husband Ken would visit on the weekends.

“Thanks to satellite images that could detect the original Trail, we walked in the same footsteps as the pioneers. When we came into Oregon City, we all looked at each other and said, ‘We did that!’ What an accomplishment to share with your friends.”

The Stingers, who also drove in their pickup the entire 2,170-mile length of the Oregon Trail in 1993, have been married 60 years, and she joked that “we are the original Ken and Barbie.”

Stinger said she has been asked if she would walk the Sesquicentennial version of the Oregon Trail again. “I would if I could,” she said. “If I was able to do it, I would.”

This past summer the Tualatin Historical Society had Tualatin Valley Community Television record a presentation by Stinger about her ancestors crossing the country on the Oregon Trail.

Trying to keep her dress dry, Barb Stinger holds it up just like her pioneer ancestors did as she crosses the John Day River.

Barb Stinger stopped for a photo while the wagon train crossed Keeney Pass.

One of the first casualties of the 1993 walk along the last 540 miles of the Oregon Trail was the feet

Barb Stinger (far right) and her friends gather for a final photo when they reached the end of the Oregon Trail.

The presentation is available for viewing at

tualatinhistory.org/programs/barbstingeroregontrail.