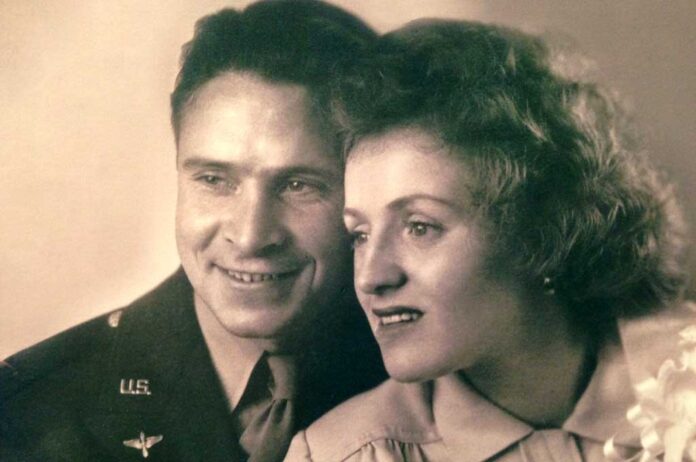

My previous two columns covered Army Air Corps Major Bradley Summers’ two B-17 crashes in WWII; the second being shot down over Germany, resulting in him becoming a POW with 22 months of captivity, primarily in Stalag 111, located 100 miles southeast of Berlin. The site had sandy soil, selected to hinder tunneling escapes. Tualatin’s Heritage Center has his memoirs, over 50 transcribed pages from interviews with him.

Summers said the Germans had respect for officers and “didn’t believe in making them work”. The officers were put in different camps than the enlisted. POWs called themselves Kriegies, short for Kriegesgefaugnen. the German word for prisoner of war. He said that Stalag III was staffed by non-flying Luffwaffe (German Air Force) officers; and enlisted personnel, generally not qualified for frontline duty. Many guards were older or had been wounded in combat. Enlisted preferred this duty for safety and living conditions but it was the least desired position for officers seeking promotion. POWs were subject to the whims of the guards and the orders of the madman who ran the country. But there was mutual respect with some of the guards, including two invited as guests to the 20-year reunion of the American Former Prisoners of Stalag III.

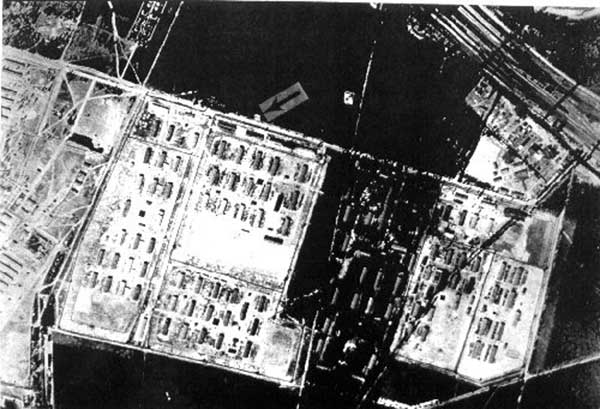

Internally each camp was run by the highest ranking allied officer who organized duties in military fashion. Summers was assigned as the Red Cross Parcells Officer for his block. They lived in barracks but “the limeys called them Cellblock, so everybody called them blocks.” At his first camp in Stalag 111, the Germans built a latrine with running water. Summers said that there were gardens and flowers planted outside the blocks. “all of a sudden, all the kriegies around the camp were watering their flowers all day ’”carrying water from the latrine facility. “Mysterious thing was that the ground in the flower beds kept rising.” An enclosure fence was near the latrine and the POWs were digging a tunnel underneath the fence to escape. “They’d gone inside there and built a tunnel. These people that were carrying water out, they would have a can almost full of sand with a little water on top. The flower beds kept getting bigger and bigger…as they watered them all day long” Unfortunately, as the tunnel reached the fence, the “ Germans came with a wagonload of coal and caved it in”

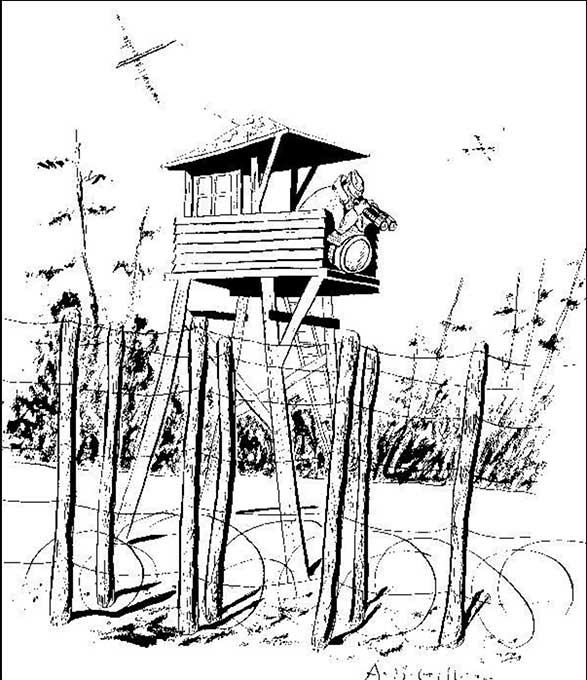

Each camp had a Committee Z, in charge of anti-German activities. The Germans used what the POWs called Ferrets. “They would crawl under the barracks and up in the attics and everywhere around” to check for anything going on that shouldn’t be”. When POWs lookouts saw them, as a warning for Committee Z activities, they would yell “tally ho”. So the Germans would not figure out the lookout system, POWs called out “tally ho” every time they saw a guard. The German guards were called “Goons” and willingly accepted the nickname after being told it stood for “German Officer Or Non-Com”. With concern about German infiltration, newcomers to each camp had to be vouched for by two POWs who knew the prisoner by sight. Those failing were severely interrogated and had several POWs assigned to escort them everywhere until deemed to be legitimate. Several infiltrators were identified through that system.

Stalag III had the best-organized recreational program of any POW camp in Germany. Each compound had athletic fields and volleyball courts. With 1,900 men in each compound, “you could find people that can do anything. Had guys with premed who ran a First Aid Station”. Had talented musicians, and actors who put on performances in a theatre the POWs built. POWs enjoyed doing pranks. Summers told about a bunkmate was known for scuffed up shoes. He and a buddy shined them up one night and put them under his bed. His friend did not recognize them and looked all over their block for them. Summers said that story was shared throughout their compound by the time the morning muster was over.

Summers generally received humane treatment as accorded by Geneva Convention. But, at Hitler’s orders, over 10,000 Staling 111 POWs were marched South in the middle of a winter storm in the middle of a blizzard in near zero temperatures as Allied Armies neared their camp. This kept them under German authority as the war ended, giving Hitler a negotiating chip. Summers’ obituary says he died on April 15, 2002, at age 82, with 44 grandchildren among his survivors. He is buried in Winona Cemetery along with his wife Rachel, brother Johnny and his wife, and his parents. Winona has 73 known veterans interned; from the Civil War, Indian wars, Spanish American War, World War I, World War II, Korean and Vietnam Wars.

Aerial reconnaissance photo of Stalag 111.

Monument for the 50 great escape tunnelers who were executed.

Map showing evacuation route from Stalag 111 so Hitler could use POWs as negotiating pawns with allied forces.

Guard tower drawn by POW Arthur Gilker.

POWs in Stalag 3 moved Northward as Russian troops close in.

Warning sign drawing by POW Arthur Gilker.