Army Chemical Staff Specialist, Sargent Herbert Smith, and his wife Beverley just loved military life. He initially joined the Coast Guard in 1952, serving three years. He was a civilian for nine months before enlisting in the Army, reporting to Fort Ord, California for basic training. They were married on July 11, 1955 and she moved to Kentucky to be near him while he received basic airborne training at Fort Campbell. Next they went to Germany where Herbert had a parachute accident. Bev said he wasn’t seriously hurt but for a while developed hives every time he jumped.

After Herbert completed his enlistment, his family missed being in the military. This time he was only out 60 days before re-enlisting, deciding to make the Army his career. They enjoyed moving around the world and the comradery with their many military friends. After a number of assignments including three more years in Germany, Herbert volunteered for a one year Vietnam tour with the 173rd Airborne Brigade so he could get orders back to Germany. Beverley said they were really looking forward to returning to Germany. But she explained, ‘Herbert was shot down on February 11, 1969 while flying through a valley in a birddog on a sniffer mission.” Severely injured, Herbert crawled out of the burning aircraft and then rolled down into a nearby creek. While looking up from the water, he saw a helicopter hovering over him, with a crewmember coming down a rope.

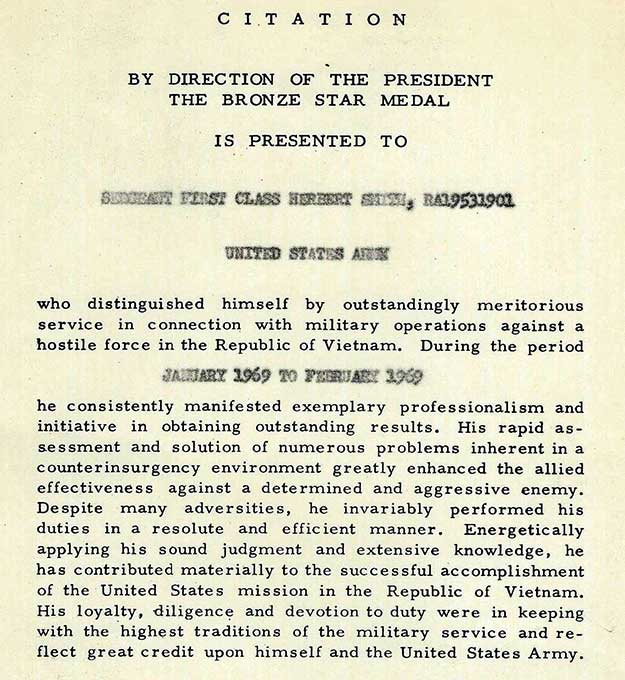

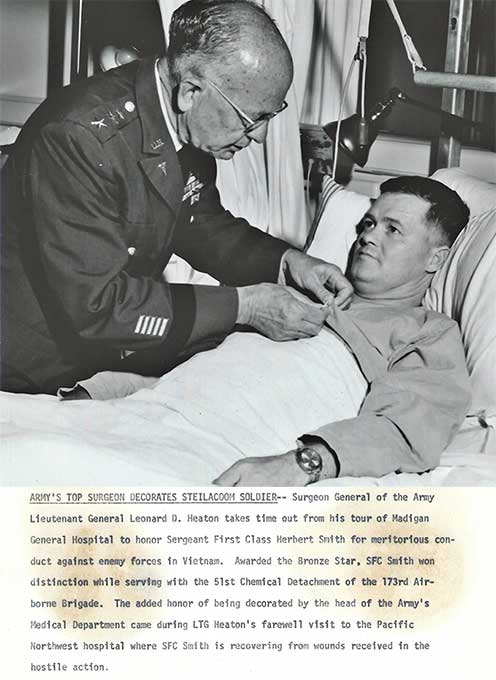

After learning that Herbert was being treated in a hospital in Japan, Bev tracked down the phone number. But when she called, he was groggy and wasn’t sure who she was. She thought, “Oh my gosh, he doesn’t want to talk to me.” But then she learned he was recovering from surgery. He was eventually transferred to the Madigan Hospital in Tacoma for a long convalescence period so Beverley moved their family nearby. Her schedule for six months was to get the kids off to school and then go to Herbert’s hospital. She said it was understaffed for the many wounded there. She helped until time to go home to prepare dinner for the kids. Her oldest daughter was 13 so after setting the kids for the evening, drove back to the hospital to see Herbert for a short evening visit. Herbert retired on August 26, 1971. He earned Bronze Star, Purple Heart, Army Commendation, Vietnam Service, Republic of Vietnam Campaign, and Air Crewman Medals.

The family moved to Portland before settling in Tualatin in 1980. Although physically handicapped, Herbert co-founded a drywall company and oversaw all the administrative work. He passed away in Puerto Rico on October 26, 2009, while on a South American cruise with Beverley.

Beverley gives a lot of herself to veteran support organizations. She is a high energy person and when talking, quickly gets to heart of situations. She is the President of the local Military Order of Purple Heart Auxiliary. She volunteers three days a week at the Portland Regional Veteran’s Administration hospital where she staffs the information booth from 7am to 4pm. She has received several awards for her volunteer work, including VAVS Volunteer of the Quarter (third quarter) for 2012. She was named the 2014 Volunteer of the Year and on June 4, received a certificate for 3,750 hours of volunteer service.

If you are in a war, you have to be able to locate the enemy. The heavy forests covering Vietnam’s mountainous regions made that difficult. Also, guerillas had dug many miles of underground tunnels which allowed the enemy to disappear while in battle. To help find the enemy, a Navy machine was redesigned that had previously swept the ocean to smell for submerged submarine exhaust fumes. Instead of diesel, it smelled the air for indicators of human presence; including ammonia particles from urine and condensation nuclei from sweat and campfires. It soon was nicknamed the sniffer. One climate factor, humidity, helped when rain washed away background scents. Reportedly, guerilla’s hung buckets of urine on tree limbs. Also, high winds, nearby civilian villages and recent firefight remains could bring false readings. High machine readings could call in air strikes, troops or artillery to force the enemy out of hiding. One crewman reported flying over a tree containing 40 or more large bird nests. The sniffer electronically sent a strong reading to a control center. The signal wasn’t corrected and the next day, a B-52 bombed the tree. It wasn’t perfect but the sniffer was the best tool our military had in that environment. Today we use satellites, drones and other high tech equipment to locate and track enemy activity; equipment that does not put our military lives at risk.