Tualatin’s Heritage Center has Summers’ WWII Memoirs, transcribed as he told his story; 48 pages of fascinating details have been sent to Library of Congress for future generations

Bradley Summers, the father of Jared Summers who lives on the Tualatin Summers family farm established by his grandfather, John Robert Summers, survived two air crashes while co-piloting B-17 Flying Fortresses in WWII. Jarad, a teacher at Hazelbrook Middle School is the only Industrial arts instructor in the Tualatin-Tigard School District.

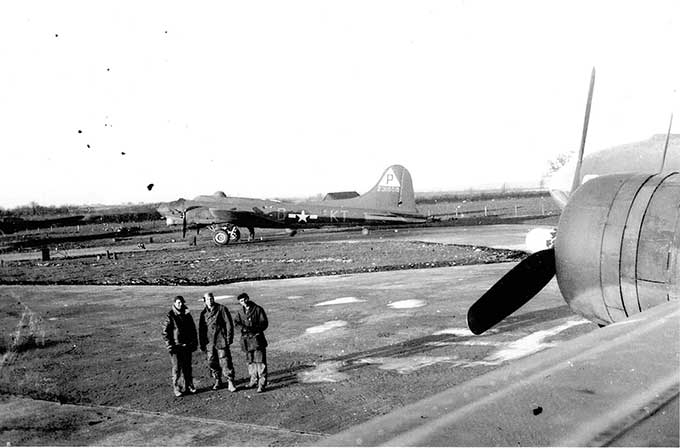

His father’s initial training was at Wendover Air Force Base in Utah. That base later was the training site of the B-29 unit that carried out the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Bradley’s aircraft crew was the first formed up for the 544th Squadron, designated Crew 41. Their squadron received the first Boeing built four engine B-17s. Among them was a plane with a serial number of 0041. That seemed to be a lucky co-incidence so his crew asked for and received that plane. Unfortunately it was not as hoped, it turned out to be a problem plane. It often had engines go out and other difficulties. Crew members gave it the nickname “ramp rat” because of the tremendous amount of time spent on the ramp for repair work. In his Memoirs, Bradley said “I think we made more three-engine landings than we did four-engine. Every time we went up something went haywire.” Those problems delayed them from flying overseas with their squadron. There was an engine change at their first stop in Nebraska. And then more difficulties at their third stop, Gander Lake, Newfoundland. At first, the weather kept them from leaving. When it cleared, as they turned on their engines, oil came pouring out of one, requiring another engine change. Finally leaving, after flying about 400 miles of the 2400 mile flight across the Atlantic to England, trouble with an engine manifold forced them to head back to land. While fixing the manifold, they flew several hundred miles before blowing out two engines, coming down near an island off the Newfoundland coast; dodging icebergs as they hit the ocean at 90 miles per hour. The crew scrambled out into two life rafts. After seven hours in frigid air, they were picked up by a Canadian J-boat. The crewmembers were so cold, they could not lift themselves out of the rafts. Their recovery was reported in the Oregonian with the headline, “10 Americans Saved from Sea.” When recovered from that ordeal, they flew across the Atlantic to England in a transport plane; reporting to war school. But Bradley said that nothing could prepare them for actual combat. On each mission, there was flack all around you as you reached the bombing site in addition to fighting off and dodging German fighter planes.

One fateful morning, Summers’ squadron, along with two other squadrons, each composed of seven planes, flew on a bombing mission to Hamburg. They utilized a “javelin formation”, placing three planes in the front element, and another three planes slightly below and behind the lead group. The seventh plane filled in behind to make a “diamond pattern”. That day, the air forces were doing what they called “a maximum effort, putting up every plane that could fly. The plan was for Summers group to turn North after completing their Hamburg bombing, and join up with another squadron that had bombed Kiel. They grouped together because each plane had about a dozen .50-caliber machine guns aboard. The combined gun power made it difficult for attacking fighter planes. Summers described that fateful flight in intimate detail. His plane was riddled with shots from a German fighter squadron with aircraft that flew at 250-300 miles per hour. He explained that “in dodging the bullets from one plane there might another drawing a bead on you and, you know, you can’t dodge them all”. His plane was being ripped apart. The most serious hits were in the tail, destroying their trim tabs and elevators (which control making the plane go up or down) making keeping the nose down difficult, making keeping the plane level very difficult. He said, “for any of you that might know a little bit about flying an airplane, they only climb at a certain speed and if you try to climb too fast, it’ll stall…the idea is to get the nose down again”. Eventually, losing control of the plane, everyone parachuted out. Bradley hit the ground hard and fell on his back. As he looked up through dazed eyes found himself looking up at a farmer holding a two barrel shotgun. Summers’ two years in German POW camps will be covered in my next columns. So stay tuned.

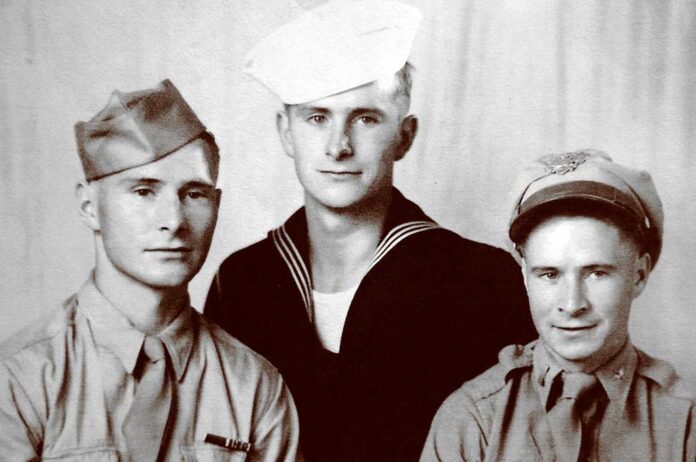

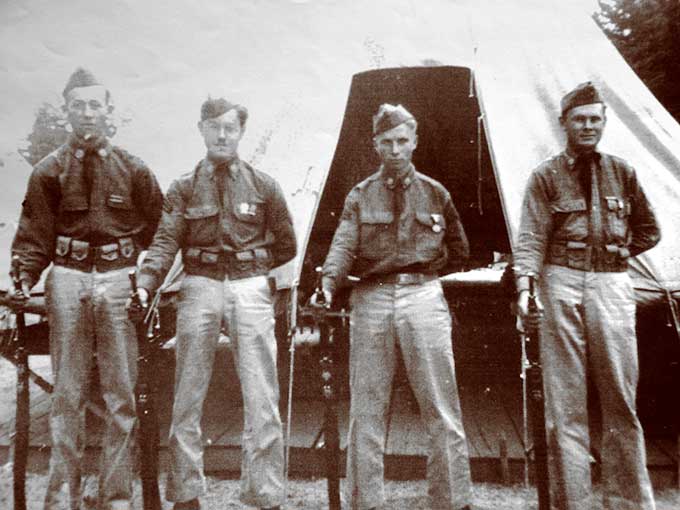

Bradley served in Oregon National Guard at Fort Stevens before WWII. He is on the left. His oldest brother Johnathan is second from the right.

Bradley and brothers (Left to right) – Brad, Tommy, Aldine ( Tommy’s wife) Johnny, Robert, and Marshall.

Johnathan on the right and Brad next to him.

Atlantic flight path. History books say Summers’ plane is the only aircraft in 384th bomb group that did not make it to England.

Mechanics preparing to repair another engine at air base.

Bradley is top right in crew picture.