This article honors the Atfalati-Kalapuyan tribe that once owned the Tualatin Valley. While I am a professional historian, I have no right to presume a tribal perspective. Therefore, I was humbled when two dedicated experts agreed to factcheck the following history and share their views. Stephanie Craig is a traditional Grand Ronde basket weaver, as well as Culture Keeper and Collections Registrar with Chachalu Tribal Museum. Dr. David G. Lewis is a member of Grand Ronde, an Ethnohistorian and Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Native Studies at Oregon State University.

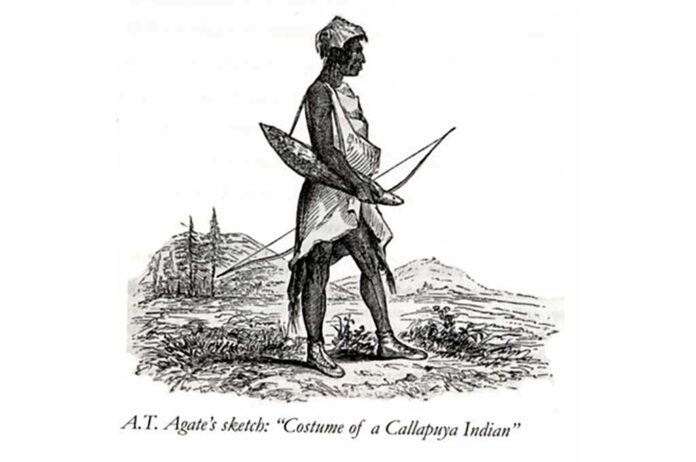

Tribal authority asserts that the Atfalati lived in the Tualatin Valley “since time immemorial” and oral histories document the Missoula floods up to 16,000 years ago. Archaeology claims a closer date of appearance circa 9,500 years ago. Family groups lived in plank-house villages near wetlands along the Tualatin River (and its tributaries), a territory that spanned from the West Hills to the Coastal Range. The tribe participated in the Columbia River trade network, especially with the neighboring Chinook and Clackamas tribes, and practiced a “stratified society with hereditary leadership positions.” Evidence of projectile points, mortars and pestles, basketry, leather and other items show they practiced complex cultural traditions.

The northernmost band of Kalapuyans, the Atfalati practiced an annual “Seasonal Round” harvesting plants, fish and game at specifically planned times. Managing the land through burning ensured soil fertility and annual regrowth. Camas bulbs that grew in oak savannahs and wetland wapato tubers were staple foods, harvested and processed for winter stock and trade. Women picked wapato by wading through the floodplains, popping up the tubers with their toes and gathering in handmade baskets. Stephanie Craig says that “We have always lived with the land, not against it. We practiced sustainable land management and used our Traditional Ecological Knowledge to promote and sustain our ways of life. We only took what we needed and could use, we never took more. If we did, the land would be out of balance and our traditional plants, our way of life would be disrupted.”

Contact with explorers in the late 1700s brought disease and foreign goods, followed by a period of economic change due to the fur trade. Malaria once again reduced the population in the late 1830s. Missionaries and volunteer militia in the 1840s, followed by the US Army and thousands of Oregon-bound emigrants in the 1850s, changed the entire landscape and way of life for indigenous peoples. Kalapuyan Chief Kiacuts tried to save the Wapato Reservation near present-day Gaston, but the 1851 treaty was not ratified. Five years later, remaining tribal members were forcibly removed to Grand Ronde Reservation west of Salem. Over time, many people intermarried and worked to save cultural lifeways and traditions, and Kalapuyan descendants are still an active part of the greater confederated tribes today.

The last person to fluently speak the Atfalati dialect was Louis Kenoyer (1868-1937). He told stories about his childhood and life on the reservation to Melville Jacobs in the early 20th century, which Henry Zenk and Jedd Schrock have recently translated. In 1954, the federal government terminated Oregon tribes. Dr. Lewis confirms that this action finalized “the complete colonization of their lands, and the loss of much of the tribal culture and most languages, including Kalapuyan, as people were forced to move to cities.”

While it is important to recognize Atfalati history and learn from the past, I also wanted to ask our experts for their perspective on tribal life and issues today. Here is what they want people to remember:

Stephanie Craig: “Our issues are still the same, we are protecting our way of life, traditions, people and future generations. We are continually fighting for our sovereign rights, we are fighting to protect the land and the plants, the water ways and the animals. But today, we have to make it in two worlds. We have to walk a thin line. We have to navigate the dominant white/Euro society and culture, but at the same time have access to the land, our ceremonies, the plants and animals; we have learned to live in two worlds. We have to purchase back our traditional lands and homelands of our people because the government didn’t withhold their end of the treaty.”

Dr. Lewis: “Our tribal cultures are a record of our familial interactions in Oregon, how we learned to live alongside the land, animals, fishes and plants as relations. That relationship with our world was severed for many when Americans colonized, took our lands and resources and moved us to reservations. It is important to Kalapuyan descendants to reconnect with their land, to carry on our traditions of stewardship and to revive a cultural relationship with the earth, so we can have a future for all people.”