When were you last in the Tualatin Mountain Range?

The Tualatin Mountain Range is one of the busiest places in Oregon but not many of the thousands of residents, businesses and tourists are aware of where they are located. Only recently did I learn from Portland State University Geology Professor Emeritus Scott Burns that I was born in the Tualatin Mountains in St. Vincent’s Hospital in northwest Portland. What a surprise for someone who grew up, worked, and volunteered my whole life in the City of Tualatin and Tualatin Valley.

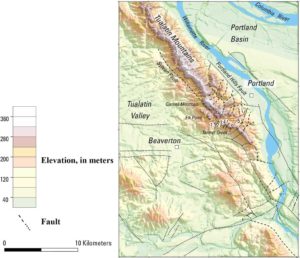

Generally you can see them from the Tualatin Valley looking at the tree lined skyline to the north and east, or from east of the Willamette River, you can see them adjacent the River, from Scappoose, behind downtown Portland as far as Canby.

Fur traders and even Lewis and Clark saw the Tualatin Mountains from the banks of the Columbia and/or Willamette River when they traded with the Atfalati/Tualatin Kalapuyan Indians. Through this mountain range the wagons of history rolled through to the Tualatin Valley via a gap now known as Highway 26, bringing wagons laden with grain for the sailing vessels that first made the Linnton area a key port.

Tualatin Mountain Range created 7 million years ago.

According to Professor Burns, the Tualatin Mountain Range begins at the Coast Range near Scappoose, follows the Willamette River south as far as the Canby delta, including the gap at Willamette Falls. They were formed from volcanic lava flows about 7 million years ago. For thousands of years, the lava flows came down the Columbia River Gorge from the east near where the Oregon, Idaho and Washington borders meet. The lava flows, known as Columbia River Basalt, created peaks ranging at least as high as 1200 feet above sea level such as Council Crest, Cornell Mountain, Pete’s Mountain; hills such as the West Hills of Portland, Cedar Hills, and gaps such as at Lake Oswego and Willamette Falls. In the Tualatin Mountains also are volcanoes of the Boring Lava age that sit on top of the Columbia River Basalt: They are Mt. Sylvania, Cooks Butte in Lake Oswego, and the volcanoes above Cedar Hills. The lava flows would have been similar to current Mt. Kiluea flows on the Island of Hawaii.

Ice Age Floods from Montana altered the local landscape 15,000-18,000 years ago.

The Columbia River Basalt lies under several feet of rich sand, silt and soils (loess) blown in by the winds over thousands more years. In addition, near the end of the ice age, Burns described even more soils, rocks and iceberg laden boulders (called erratics) were brought to the Tualatin Mountain foothills by at least 40 cataclysmic floods. The floods resulted with the melting and breaking of an ice dam holding back Lake Missoula. Each time, the lake waters emptied across Idaho, Washington and down the Columbia River Gorge. They traveled at speeds up to 60 miles per hour down the Gorge on their way to the Pacific Ocean but a basalt barrier at Kalama, Washington restricted the flow and backed the flood waters along the Tualatin Mountains as high as 400’ in what is now downtown Portland.

The raging flood waters entered the Lake Oswego gap of the mountain range and scoured out the lake before proceeding west into the Tualatin Valley going as far as Gaston and Forest Grove and the Yamhill Valley past McMinnville. They then raged further upriver and entered the Willamette Valley through a second gap in the Tualatin Mountains at Willamette Falls.

The 350-400’ high ice age floods waters backed up the Willamette River as far as Eugene, carrying the rich soils, debris and erratics (rocks that don’t come from here). The rich soils attracted pioneers to Oregon and are still key to Oregon’s agriculture. One note is that most current vineyards are placed above the rich soils 400’ elevation line in the valleys to keep the grape vines producing the flavorful grapes rather than mostly leaves and bushes. At the end of the ice age, over 12,000 years ago, ancient animals such as mastodons, mammoths, giant sloths, and bisons are a few of the ancient animals which lived on the land, proved from bones that have been found in the Tualatin, Willamette and Yamhill Valleys and radio-carbon dated. Many bones are being discovered and University of Oregon Museum in Eugene is a depository for the bones.

Mountains Named after Atfalati/Tualatin Kalapuya Tribe.

The Tualatin Mountain Range and Valley were probably named after the Atfalati/Tualatin Kalapuya Tribe. David G. Lewis, Anthropologist and tribal member of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde stated the tribe had their own autonomy. The name was pronounced “Uh tfalati” according to Henry Zenk, Linguist and consultant to the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde. According to recent discoveries, Native Americans lived in the Northwest at least 14,000 years ago (Paisley Caves site-oldest site in Oregon).

The Tualatin Mountains appear on an 1855 “Sketch Map of Oregon Territory”, describing the location of lands owned by various Indian tribes and their territory. The map includes the Tualatin Mountain Range and the Tualatin Valley as being the lands of the Atfalati/Tualatin Kalapuyan Indians. The Mountain Range appears to have been included as part of the Dayton Treaty when several tribes gave up their lands to the United States of America and were moved to the Grande Ronde Reservation. The map was acknowledged by the U.S. Geological Survey Research.

Loss of identity of this Mountain Range on maps not a new problem.

The entire range doesn’t appear on any recent maps that I can find. They were partially shown on USGS maps over 50 years ago but not currently. The loss of identification of the entire Tualatin Mountain Range on state and federal maps is not a new problem. I made calls last year to U.S.G.S staff which confirmed their existence and said they can be put back on maps at their discretion but to date that hasn’t happened. Even though the area’s major television stations have 4 or 5 towers on the Tualatin Mountains that can be seen above the skyline, the TV stations’ weather forecasters do not show the Range.

Oregonian Reporter wrote about the absence of Tualatin Mountain Range on maps.

In a 1957 Oregonian article by Leverett G. Richards, obtained from the Oregon Historical Society, he wrote in part, “While the Tualatin range of mountains might be considered miniscule in a land of mighty mountains like the Northwest, it would be considered a whipperdilly anywhere east of Denver. It is a range of which to be proud.”

Richards further wrote: “The City of Roses is also a City of Mountains, a whole range of mountains, thanks to H.B. Schminky, Portland city surveyor and the U.S. Geological Survey. Actually Portland owned some of them all along, but the whole range-now officially known as the Tualatin Mountains-has been lost for 100 years. Generations of Portlanders have been born and raised on the peaks of this range but have belittled these mountains with such pusillanimous pseudonyms as “West Hills” and Portland Heights.”

He then described the Tualatin Mountains “Spread”: “Starting almost in the heart of the metropolis is a range of mountains extending for 35 miles and covering about 200 square miles of country. Curling casually westward, the Tualatin Mountains spread out into rugged canyons and summits rising to 2033 feet in Pisgah Mountains and 2225 feet in an unnamed point southwest of the old mill town of “Bacona”.

Further, he described in part, “how they rise sleepily from the bank of the Willamette at Oregon City, gradually stretching up to a respectable 450’ or so at Iron Mountain on the north shore of Oswego Lake, thence to 1020 feet in Mt. Sylvania, two miles further north, then inspired by the example of Mt. Hood in the distance, then hump up to 1073 feet at Council Crest, 1260 feet at Barnes Heights. Thence, these metropolitan mountains broaden out to eight and ten miles in width and wander amiably northward out of the city limits to a new crest of 1609 feet in Dixie Mountain, just north of the point where Skyline Boulevard becomes Rock Point Road, in the far northwest corner of Multnomah County.”

Things to see and do in the Tualatin Mountain Range

You are in the Tualatin Mountain Range when you are on highway 30 which hugs the mountains north of Portland, starting just south of Scappoose. That area is known as the North Tualatin Mountains and includes Forest Park. The St. Johns Bridge is at the foothills. Travel behind downtown Portland (commonly known as Portland’s West Hills), through Lake Oswego and West Linn to Willamette Falls and Canby, near the Canby Ferry. From I-5 you can see them all the way from Wilsonville (Pete’s Mountain) to the intersection of 217. And from the I-5/I-205 intersection at Tualatin, you are soon in the Tualatin Mountains as far as West Linn and can see the Willamette Falls and Mt. Hood just before you cross the Willamette River.

From downtown Portland, proceed west through the tunnels under the Tualatin Mountain Range, (Highway 26-Sunset Highway) or ride the light rail cars through more tunnels to the Tualatin Valley. Or you can now take an aerial tram ride from the Willamette River, pass over I-5 to Marquam Hill’s University of Oregon Health & Science hospital and enjoy the magnificent view from the Tualatin Mountain Range. Just some of the highways run through the mountains: I-5, I-205, Hwys. 8, 18, 26, 30, 99W, 99E, Barbur Blvd, Canyon Road, Terwilliger Blvd, Taylor’s Ferry Road, Boones Ferry Road. Highway 26 was the first plank road allowing people to bring products to market through the Tualatin Mountains to the Willamette River docks and communities. The highway was later tunneled through the mountains.

Unusual and interesting attractions worth seeing.

Oregon Travel talks about the 7 Wonders of Oregon. I have counted at least 70 within the Tualatin Mountain Range. Here are just six that seem to be more or less hidden also but each site provides an important history lesson for all ages: 1) Canby Ferry on Willlamette River; 2) Willamette Falls at I-205 overlook (and Mt. Hood in distance)-not far from where the Oregon Trail ended at Oregon City. 3) Field’s Bridge Park on the Tualatin River which describes the ice age floods and near where the Willamette Meteorite, the fifth largest in U.S. was found after it floated in an iceberg during the ice age floods; 4) way down in the canyon below the TV towers is the Willamette Stone where the first survey of all Oregon lands began and where Meridians (north/south lines)-Meridian Park Hospital is on a meridian separating Washington and Clackamas counties) and Baselines (east/west descriptions to Idaho and Pacific Ocean at Bay City) were established in late 1800s.. 5) At the Oregon Zoo, a geologic stratigraphic column can be studied by taking an elevator down into the Tualatin Mountain Range where the Metro light rail picks up riders going to the Tualatin Valley or downtown Portland. 6) On a drive along Skyline Ridge of the Tualatin Mountain Range, from the Zoo area to Scappoose, you can see the Portland Basin on one side and the Tualatin Valley on the other.

Hundreds of trails, parks, universities and colleges and wonders are located within the Tualatin Mountains.

They include the hundreds of natural acres of Portland’s Forest Park, Oregon Zoo, Rose Gardens, Portland’s West Hills, Forestry Center, Camassia Nature Park owned by the Nature Conservancy in West Linn, Oregon Golf Club on Pete’s Mountain; OHSU campus on Marquam Hill, Portland State University and some parts of downtown Portland in the foothills; Portland Community College on Mt. Sylvania; Lewis and Clark University. Even Marylhurst University is in the foothills and Iron Mountain is where iron was first obtained for the iron smelter at Lake Oswego. And yes! Even the current St. Vincent’s Hospital at the end of Highway 217 is in the foothills of the Tualatin Mountains.

So now you know when you were last in the Tualatin Mountain Range.

The only mystery remaining is why they disappeared from Oregon maps, television weather reports, etc. and how they can be put back on so another 100 years doesn’t pass and they are lost to history forever. As Oregonian reporter Leverette Richards said 59 years ago, “the Tualatin Mountain Range is a range to be proud of”